The Unmeasured, Chapter 4: The Deportation

A Father’s Exile, a UFO’s Silence, and the Search for Forgiveness

Patrick Neitzel was not a man anyone expected to slip into the margins. He grew up in Germany as the son of Karsten Neitzel, one of Germany’s most respected football coaches, and carried the steady discipline of sport and family name into adulthood. In his own life he chose service, becoming a customs officer with the German state, a job that promised stability and permanence. By 2009 he was married, living in Oregon with his wife, Crystal, and their young son, carving out a life that looked ordinary from the outside and felt solid from within. It was a family built on daily routines – the airport runs, the paperwork, the small joys of raising a toddler. And then, in a single layover, it came apart.

Airports are built for flow. Families move through them like rivers, branching into lines, merging again at the gate. In 2009, at Atlanta, the Neitzels split. His wife and toddler moved easily into the citizens’ queue – familiar, automatic, the quick stamp of a passport and then home. Patrick joined the other line. The slower one. The one that carries the implication that you do not quite belong.

The officer took his passport and didn’t give it back. A nod, and Patrick was guided into the secondary room. There are no windows in those rooms. The clocks never seem to move. Time becomes something that happens to other people.

He waited on the bench. They called his name, asked questions, sent him back. Then called him again. Hours passed this way. The toddler was somewhere on the other side of the glass, probably restless, probably asking for his father. Patrick tried not to think about it.

Finally an officer held up the visa. Perfectly fine, stamped, current. Then he took out a pen and drew a line through it. Big black slash. Canceled. Looked up at Patrick, smiled, said: “Now you don’t have one anymore.”

Patrick waited for the joke to land, for the part where the officer would say, just kidding, relax. But no. The smile stayed. The line stayed. The visa was now just paper with ink on it.

Next came the forms. Amazing things, these forms – whole alternate lives conjured in a few keystrokes. Patrick was now from South Korea. His visa was invalid. He had supposedly waived his rights. None of it true, all of it official.

So here’s the deal: sign the lies, or sit in custody indefinitely. Those were the options. Buried deep in the paperwork was the line that said he had been born in South Korea – a fiction slipped into the fine print – and with it, the quiet revocation of his right to ever return to the United States. He didn’t see it then. He couldn’t. Exhausted, intimidated, desperate to get out of that windowless room to see his family, he signed.

He did not see his family again before they boarded. His wife took their son onto the flight to Portland, alone. Patrick was put on a different plane – back to Europe, back to Germany.

That was the real wound. Not the officer’s smirk, not the lies on the page, not the word illegal suddenly stapled to his name. The wound was the boy who would keep growing without him. Birthdays missed. First days of school. Afternoons that turn golden in memory because you were there – except he wasn’t.

He told himself it was bureaucracy, not betrayal. But guilt doesn’t care about the reason. It sets in like bone, stubborn and permanent. Years later, when the psilocybin came, the first words he heard were the ones he least wanted: it wasn’t your fault.

The Triangle

Four years passed. By 2013 Patrick Neitzel was back in Germany, carrying the weight of exile on his shoulders and trying to stitch together a life that no longer fit. The absence of his son was a wound that didn’t close, the ache in his back a constant reminder of years spent fighting his own body. He even tried to appeal to Congressman Kurt Schrader of Oregon’s 5th District, reaching out through a personal connection. But after a brief flurry of interest, the office told him there was nothing they could do, and so the silence deepened.

Crystal had drifted back into his life by then. Years earlier she had nearly followed him to Germany for good, but she pulled back, and they separated. After his deportation, though, and the fracture of his marriage, she returned in fits and starts. There were signs she was carrying her own hidden battles, though Patrick didn’t yet understand how deep they ran. She visited, sometimes staying even when his girlfriend was also in the house – an arrangement most people would have found impossible, but one Patrick endured with the same stubborn patience he brought to every burden. By 2013 she was spending more time in Germany, present during his long shifts with the customs service, helping where she could with his son, and sharing evenings at his parents’ home in the German countryside.

His parents’ home sat on the edge of Freiburg, a sturdy house with its back to the fields and its windows opening toward the Rhine. The land rolled gently down to the river, the air smelling of wet grass and stone. In the distance, past vineyards and clusters of trees, rose the towers of Fessenheim, France’s oldest nuclear plant – close enough to see on a clear day, close enough that you could imagine its hum if you let yourself. It was a landscape both beautiful and uneasy, a place where orchards and forests stood side by side with the machinery of catastrophe.

That summer night he and his girlfriend Luisa stood outside in the back, talking quietly about his son. A pack of Lucky Strikes lay between them, the paper burning down fast in the still air, smoke curling and vanishing above the garden pool. The conversation was tangled and heavy, but for the moment they were together, mid-sentence, when the silence fell and the sky opened.

He thought at first it was a star. Too bright for that sky, too clean. A spotlight, maybe, angled wrong, catching his eye from above. He studied it and then saw there were not one but three points, fixed and equidistant. They did not blink. They did not waver. They simply held their place against the night.

And then the world broke.

The lights came down fast. Faster than thought. If you had blinked, you would have missed the descent. One instant three dots hung against the horizon, the next a black mass filled the air above the neighbor’s house.

The triangle was black. It hung in the dark.

It was big, thirty feet to a side, the span of the house itself. An equilateral form, its edges perfect, its skin a matte absence of light. In each corner a lamp burned, super bright, though never blinding. He did not need to squint. He could not look away. The beams glowed but cast no visible spill across the yard, as if illumination itself had been suspended.

Here’s the part that’s hard to put into words. The damn thing just sat there. Only it wasn’t “sat there” the way a plane idles in the sky, or a chopper hangs with its blades chopping the air. No, this was different. It was like the air itself had locked up around it, like the universe hit pause. You know how a hummingbird looks still when it hovers, until you really look and realize it’s working like hell to stay in one place? This was the opposite. The triangle wasn’t working at all. It was just there, and the stillness of it made the whole night feel wrong, like you’d stepped sideways into somebody else’s dream.

The night had been ordinary, marked by conversation, a running garden pool, the small insistence of frogs and insects. Now everything had gone. No crickets, no frogs, and no water sound. Not even their voices. He and Luisa had stopped mid-sentence, the silence arriving like a lid pressed over the world. Later he would learn there was a name for it – the Oz factor – the strange stillness that comes when the air itself feels locked.

They just stood there, rooted, necks craned back. The thing – if you even want to call it a thing – hung over them like it had all the time in the world. Not moving, not twitching, not making a sound. Just there. And the worst part wasn’t the quiet. You can live with quiet. It was the feeling that the quiet was looking back. Like the night itself had eyes, and it had picked you.

The craft seemed to be looking at them, belly first. Watching.

Time loosened. Seconds or minutes passed, impossible to know. Luisa remembered it as short, but for him there was no measure. There was only the shape and the weight of its presence, a thing that should not exist holding its place in the night as though it had always been there.

And then the craft departed.

It did not accelerate the way human machines do, with the protest of engines or the gradual accumulation of speed. It simply occupied a sequence of positions that logic declared impossible. From one point in the sky to another, it traced angles that would have destroyed any structure we could build, but it held its form without effort. Each shift left a faint streak, not in the air but in the eye, as if human perception itself could not quite refresh quickly enough to keep pace.

What Patrick saw was not motion but the collapse of continuity – a series of positions stitched together into the appearance of movement, the way a film projector tricks the mind into seeing life where there are only frames. Except this was no illusion. The object was there, and then there, and then gone.

The silence was total. The garden returned to itself: the pool, the grass, the faint smell of cigarettes. But the sky was altered now, not because the triangle remained, but because its absence had proven something. It had shown them a law of nature bent like a reed in the wind, and then it had withdrawn, leaving no evidence but memory.

Patrick: The Man

Patrick was not a man who went looking for visions. He was a customs officer, sworn to the routines of the German state, with the assurance of lifelong employment and the burden of lifelong duty. He carried himself with the plain confidence of someone whose life was set in motion by institutions, not fantasies.

What complicated that picture was his role as a father. He was raising his son largely on his own, through turbulence that had broken apart his marriage and left him improvising a kind of double life: enforcer by day, caretaker by night. He worked to sustain order, then came home to a boy who needed him to soften into something gentler. It was not a glamorous story. It was the story of many men who find themselves unexpectedly alone with children and responsibility, unsure whether the weight will build them or break them.

The sighting in his parents backyard was not only the intrusion of something alien into his skies. It was the interruption of a man’s very sense of proportion. How could he tell a child, already navigating the fragility of a broken home, that the universe itself had revealed a fracture? And yet it was the child who anchored him when others mocked. Friends might turn away, colleagues might dismiss his story, but a father does not lie to his son.

The tragedy, and the beauty, was that Patrick’s credibility mattered most in the one place it was never questioned: in his own kitchen, with his son.

The Aftershock

Only later did he realize what lay in that direction. Less than two miles away, on the French side of the Rhine, stood the Fessenheim nuclear plant. It was notorious: the oldest reactor in France, riddled with safety complaints, perched uneasily on a fault line. Locals had spent years petitioning for its closure.

The triangle had appeared above his neighbor’s roof, but it was also above that plant. That was the line of approach, the silent corridor it traced through the night.

The pattern is too consistent to dismiss. From Malmstrom Air Force Base in Montana to Chernobyl in Ukraine, from Fukushima to the missile fields of North Dakota, unidentified craft have been recorded around nuclear facilities. Always the same behaviors: sudden appearances, hovering, power failures that no engineer can fully explain.

It is hard to believe this is coincidence. Harder still to believe it is meaningless.

Patrick stood there in silence, thinking only of what he had seen. He did not yet connect it to the reactors. But in retrospect the logic was brutal. The most dangerous thing man has built, the machines that can poison the earth for centuries, attract the attention of whatever else shares the sky.

And there’s something absurd about it too: the idea that this creaking old plant, humming and leaking, was important enough to draw the gaze of a triangle that moved faster than thought. Like some bureaucratic office building suddenly being inspected by gods.

In the days that followed, sleep did not come easy. When it did, it came strangely.

The day after his triangle sighting, he took a nap at noon. He came awake all at once and knew something was wrong. His chest felt like someone had parked a truck on it. His arms and legs were nailed in place, useless meat, and his mouth hung open like he’d forgotten how to close it. He tried to shout, and nothing came out. He tried to move, and his body didn’t care.

What he remembers is waking, or thinking he woke, and feeling it: a presence. Out of the corner of his eye, there was something in the doorway. Just a shadow, faceless, featureless, like a cutout where a person should be. And that was when the fear hit, and the kind that slides cold down your spine before you even know why.

He tried to look, tried to move, but couldn’t. Every nerve was locked. His body was a coffin, and he was trapped inside. Panic banged against his ribs while the shadow stood there, patient as stone.

And then, release. Not the kind you want. He could move again, but it was wrong. He wasn’t in his bed anymore. He was at the ceiling, pressed close to the wall, floating like a balloon that had slipped its string. He turned his head – slowly, impossibly – and looked down.

There he was. Himself.

Sprawled on the bed below, mouth slack, chest rising and falling.

“Holy fuck,” he thought. “That’s me.”

The realization snapped something deep inside him. A gut-level alarm went off, the kind that doesn’t care about logic or philosophy, just survival. The fear was too much, too sharp, and in an instant he was yanked back down, slammed into his body like a diver hitting water wrong.

When he sat up, the shadow was gone. No trace, no sound. Just the room, quiet and ordinary. Too ordinary.

He told himself it couldn’t have been a dream. It hadn’t felt like a dream. It was too vivid, too wrong. He knew the difference. Whatever it was, it wasn’t sleep. It was something else, something he couldn’t name, and maybe something he wasn’t supposed to survive.

Weird as hell, he said. And you could tell by the way he said it that the weirdness hadn’t let go of him, not really, not after all these years.

“I had an absolute feeling of panic,” Patrick said, “and it was like I was sucked back into my body, and then I was like, I can move. I was in my body, and this felt so real. It was…it felt so real.”

Later, when he read John Mack and Robert Monroe, he’d realize people had names for this – sleep paralysis, out-of-body, the soul taking a walk. But lying there in the dark, sweat cooling on his skin, he only knew one thing: he had been out, and then he was back, and there had been a second where he wasn’t sure which version was going to stick.

The Psychedelic Release

Patrick Neitzel was, above all else, a man of duty. He was the son of a football coach whose career was built on discipline and respect, and Patrick inherited that same bearing. He chose service early, committing himself to the German customs service and the long, steady grind of state employment. It wasn’t glamorous work, but it mattered – inspections, investigations, the constant need to keep the borders honest.

He drew a sharp distinction between his work and what Americans imagine when they think of “customs.” His job was not anything like the American ICE. It was not night raids, deportations, or families ripped apart in airports. German Zoll is a different institution altogether – a career built on steady rule enforcement, the protection of financial markets and communities, and the kind of quiet integrity that Germans expect of their civil servants. Patrick took pride in that. His work was meticulous, bounded by law, and never defined by cruelty.

What truly defined Patrick, though, was fatherhood. His marriage unraveled not out of malice but under the weight of pressures neither he nor his wife could master, and in time she succumbed to addiction. He never spoke of it with recrimination, only with sorrow: a recognition that life can crush even the strongest spirits, and that what falls is not always weak but often simply overburdened. Out of that collapse came the moment that would define him most – the decision to raise his son alone.

From that point forward, Patrick’s existence was cleaved into two stark halves. By day he wore the uniform, a servant of the German state, a man sworn to order and steadiness, making sure the world beyond his front door remained intact. And by night he returned home to a smaller, more fragile world, one in which dinner had to be cooked, homework supervised, nightmares soothed. He bore not only the responsibility of a father but also the tenderness of a mother, folding both into himself because his son required both to thrive.

All of it was done through pain. His back, injured years earlier at the academy, had never truly healed. The ache was constant – a dull, grinding companion that no morphine could entirely silence. It bent his posture, slowed his movements, shadowed his days. And yet he did not let it shadow his son. He bore it the way he bore everything else: quietly, determinedly, refusing to let suffering absolve him of duty.

It was not a glamorous life, nor was it easy. But there was honor in the relentlessness with which he embraced it – in the quiet heroism of a man who, abandoned by institutions and betrayed by circumstance, still showed up each day to love his child. To see Patrick across the table from his son was to see not merely survival, but devotion distilled to its purest form.

He admitted the exhaustion to me – the endless cycle of work, meals, and sleepless nights – but he never once described it as a burden. “I had to be there for him,” he said simply, as though it were the only option. Friends and colleagues could dismiss his stories about UFOs, but his credibility mattered most in the one place it was never in doubt: across the kitchen table from his boy. He is a man who had carried both state duty and family duty with the same steady hands, no matter how strange his story became.

For years, that steadiness kept him from seeking help. He dismissed psychedelics as dangerous, old stories clinging to his mind: people leaping from rooftops, losing themselves in madness. But the studies kept surfacing – Johns Hopkins, Berlin, Oregon – and eventually he read them all. At last, after a decade of pain, he decided. He prepared the way he would for police work: carefully, methodically. He researched peer-reviewed studies extensively. He set out playlists, coloring books, even antidotes on the table, in case things went wrong. He found a way to try this form of healing without breaking the law. He wasn’t looking for visions. He was looking for reprieve.

At first nothing happened. Then everything did. Darkness gathered at the edges of his mind, heavy and complete. Out of it came a voice. It was not loud, but it was absolute. Forgive yourself, it said.

He resisted. He told it there was nothing to forgive. He had never struck his son, never abandoned him, never ceased to love him. His only crime had been absence – birthdays missed, first days of school unseen, the slow drip of time that bureaucrats and borders had stolen. But guilt is not rational. It lives in the body, in the spine that will not straighten, in the ache that no medicine will quiet.

The voice returned, patient, unyielding. Forgive yourself.

And then he wept. He wept for the boy who had needed him, for the years that would never be returned, for the way absence feels like betrayal even when it is not. And at last he said the words out loud, words he had never allowed himself to form: I forgive myself.

The knot that had lived inside him – the twisted bundle of pain and shame and love unexpressed – broke open. He saw it dissolve in radiant color, like powders cast into the air at a festival, each particle burning briefly before fading into light. His back released. The clamp that morphine had never touched simply let go. His body straightened; he breathed without pain.

The visions that followed were lessons, but this was the revelation: that love does not collapse under distance, that fatherhood can endure across absence, that even the most stubborn guilt can be untied.

And then came the lights. They were the same lights. The triangle that had once hovered above him, impossibly still, impossibly fast, now revealed itself from within – the same intelligence that had silenced the night now loosening the silence in his body.

When he returned, the pain did not return. He would call this the most profound experience of his life, second only to the night the triangle descended. But it was the forgiveness, not the visions, that saved him.

The Cost of Telling

When he spoke of it, people laughed. Not with him, but at him. He was a man sworn to truth, a servant of the state, and still his words turned to folly in the mouths of others. Friends turned away, colleagues smiled behind their hands. He had stood in the presence of the incomprehensible, and yet it was not the vision that shamed him, but the telling of it.

This is how cruelty often works: not in the thing itself, but in what the world demands you feel about it. The ridicule was not proof of his madness; it was proof of their fear. For it is easier to laugh than to believe, easier to dismiss than to face the weight of another man’s witness.

And so for a long time, he carried it alone. Alone, except for the boy. His son did not ask for evidence. He did not sneer at the silence or the streaks of light. He listened, because children know that the world is strange, and only later are they taught to deny it. In his son’s presence, Patrick’s testimony was not absurd but sacred.

What mattered, finally, was not the jeers of his peers, but the trust across that kitchen table. To be believed by one person who loves you is a greater vindication than the acceptance of a world determined to make you doubt yourself.

It is always the same lesson, written in different alphabets: a man can be mocked for telling the truth, but he cannot be robbed of the truth he has seen.

Rebuilding Memory

Years passed, and the triangle didn’t return. Memory is a fragile machine, unreliable in the best of times, and he feared it would decay the way dreams do, breaking into fragments until only the vaguest impression remained. What he had seen was absolute, and yet it lived only in the wet circuitry of his own brain. That seemed intolerable.

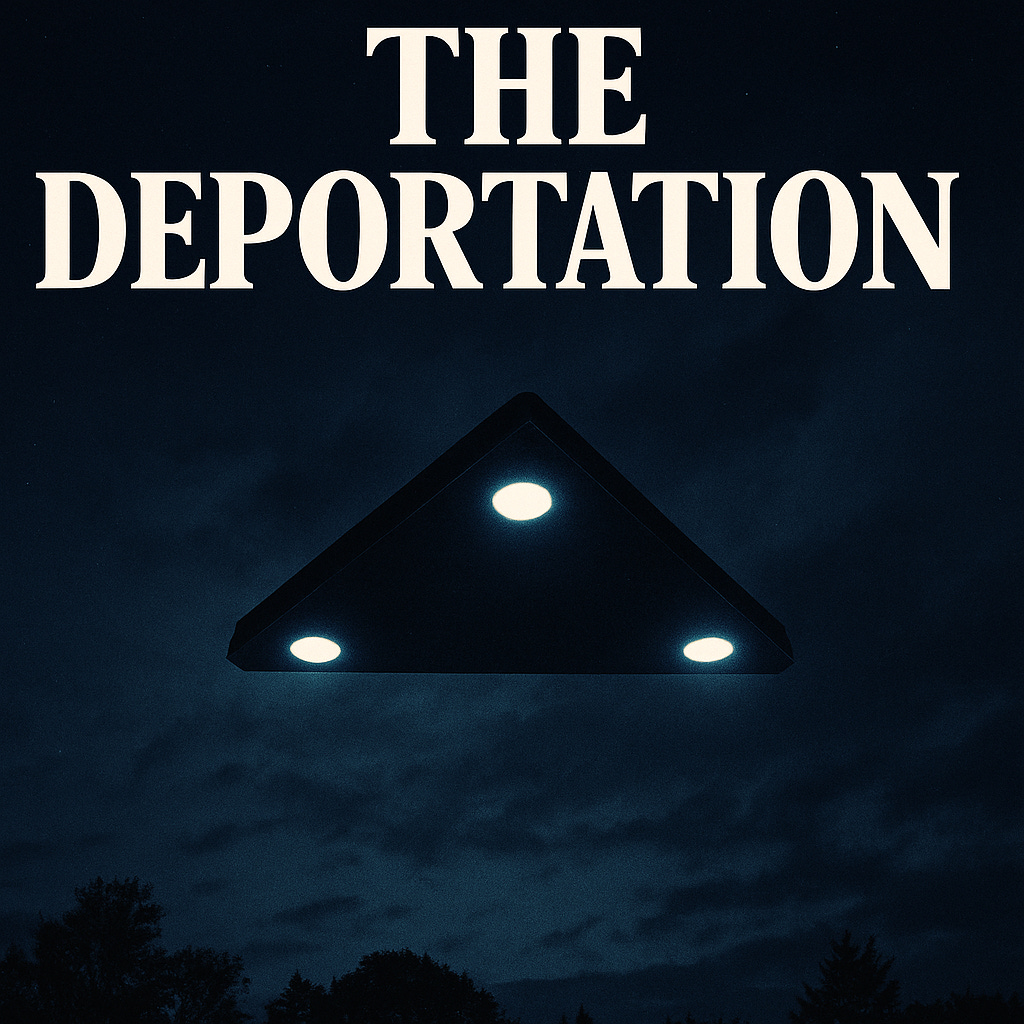

So he did what men do now, in this century: he went online. Somewhere out there was another man who had seen what he had seen. His name was Fin Handley. Fin had already drawn his own memory into being – a computer image of a black triangle suspended over a roofline, each corner lit with a glow that cut without shining. Patrick reached out, and they talked. Strangers at first, then not.

Together they rebuilt his night. Fin shaped the sky, the roof, the triangle, until Patrick could look at the screen and feel that old silence come back. It wasn’t evidence for anyone else. It was a way of holding on, of refusing to let memory erode into doubt. Fin would later become one of Patrick’s closest friends.

In the end, it was less about proof than survival. To see again what time had been stealing was to reclaim it, if only for himself.

There was something unbearably sad about it. Like one of those irony-poisoned moments where you realize you’ve gone to such extraordinary lengths to make people believe you, and still no one will. A triangle that defied physics, rendered as a YouTube clip, destined to be scrolled past.

The paradox is merciless: the real thing is impossible to prove, while the fake thing can be made photoreal with ease. The hoax thrives; the witness is ridiculed. Reality and invention trade masks, and the crowd always prefers the mask.

He looked at the animation and thought: yes, that is what I saw. And then, just as quickly: no, it isn’t. It can never be. Because what hovered over him was not merely visual, but existential. It was presence. It was silence. It was the feeling of being studied by something that didn’t care if it was remembered.

As Fin Handley once said, “UFOs don’t pose for selfies.” They leave you with memory, and memory is the most fragile evidence of all.

Below is the CG rendering of Patrick’s encounter:

Karolina

What saves Patrick, finally, is not the US government that cast him out nor his friends and relatives who have met his story with silence or ridicule, but his wife of more than ten years, Karolina. She does not laugh at him, not even gently, not even in private. She believes him, which is more than he has ever dared ask of the world. Hers is a faith not born of credulity but of love, the kind of love that understands belief itself can be an act of shelter.

Karolina’s Catholic upbringing might have taught her to question visions, to weigh them against doctrine. Yet she never lets that background place itself between her and Patrick. She does not parse his testimony for orthodoxy or dismiss it as fantasy. She listens, she holds, she honors. She has no public voice in this, no pulpit from which to defend him. But she is there – wholly, quietly, reliably. And that is the truest defense a man can have.

He knows with her he need not conceal anything. The exile, the broken marriage, the constant ache of his back, the endless worry for his son, even the impossible story of the triangle in the sky – all of it can be spoken, all of it can be carried into her presence without fear. She has accepted every circumstance, every piece of him: the father, the ex-husband, the civil servant, the man branded “crazy UFO guy.”

She has made of that acceptance something steady, a harbor into which he can finally come ashore. Karolina is not simply his wife. She is his refuge.

Greg’s Reflection

To live through something inexplicable is to find yourself forever exiled from the ordinary community of the explained. Patrick’s triangle was not only a craft in the sky but an opening in the fabric of his life, and tears of this kind never mend neatly. They leave one half tethered to this world and half to another, distrusted by both.

His story reverberates in a larger pattern. Triangles hovering above nuclear plants, discs above missile fields, lights pacing our fastest jets. Always the same response: denial from the state, derision for the witness. As the CIA’s 1953 Robertson Panel and other revelations made explicit, ridicule was not an accident but a chosen policy: debunking as psychological warfare, the cheapest way to contain the subject. Richard Dolan has shown how that strategy hardened into decades of silence, a cordon sanitaire around the subject. Orwell taught us that control of language is control of reality, and the same logic still governs here: to laugh at the witness is to erase the event.

But the greater significance is not in the state’s repressive cunning. It is in the witness who refuses to collapse beneath it. Patrick carried the triangle into his aching back, into the loneliness of separation from his son, into the long nights when psilocybin finally coaxed release. The presence he saw suspended over the Franco-German border was the same presence that whispered from within: something that studies, that observes, that does not apologize.

Dr. John Mack’s own analysis of “ontological shock” warns that the recognition of a nonhuman intelligence could unsettle not only governments but the very legitimacy of our anthropocentric order. Patrick lived that shock at the most intimate scale. He bore the fracture in his body and mind long before any government confessed its existence.

There is a quiet nobility in that. To testify to what you have seen, even when institutions mock you. To admit that the world is larger than the categories we use to contain it. Patrick’s account is not just about lights in the sky. It is about the cost of seeing clearly in a culture that prefers the comfort of disbelief, and the strange grace that comes when you accept that truth does not depend on recognition.

He saw it, and they did not.

They ridiculed him, and still he spoke.

The silence of the craft became the silence of his life.

But silence could not annul the fact:

It was there.

He was there.

And that endures.

To have a profound and deep experience like this, only ro have friends and family reject what you saw, or attempt to explain it away, sucks, for lack of a better way to put it. Thank you, Greg, for giving us your ear and open mind, the willingness to hear our stories and to tell them.

Another beautifully written experiencer story, Greg! That the US Gov’t would cancel his visa without a good explanation, which would land him in Germany on that fated day to witness the triangle is incredible. Sometimes we don’t fully understand why we’re put through the gauntlet of certain life challenges…. Until we do 🙏🏻